Usually, when something in nature turns pink, it’s not a good sign. But strange pink sands washing up on South Australian beaches have revealed an ancient Antarctic mountain range thought to be buried beneath the ice.

When streaks of pink first appeared in the sand at Petrel Cove, a remote beach that meets the Southern Ocean, scientists in Australia quickly discovered what the colored sand was made of, a mineral called garnet, but were surprised by his age and where originally from.

“This journey started with the question of why there were so many garnets on the beach at Petrel Cove,” says University of Adelaide geologist Jacob Mulder.

“It’s fascinating to think that we were able to trace tiny grains of sand on a beach in Australia to a previously undiscovered mountain range under the Antarctic ice.”

The earth’s crust is constantly eroding and reforming, with loose sediments blown away by wind and water deposited elsewhere to form new soils. If geologists are lucky, they can establish connections over great distances and long periods of time between deposits of similar ages with similar properties.

Garnet is a fairly common mineral, with a deep red color. It crystallizes at high temperatures, usually where great mountain belts are ground up by colliding tectonic plates. This makes it perhaps the most important mineral for inferring how and when mountains formed, as the presence of crystals tells the pressure and temperature history of the metamorphic rocks in which they form.

The team’s lutetium-hafnium dating showed that some of the garnets found at Petrel Cove and nearby rock formations matched the timing of local mountain-forming events in South Australia.

But their results show that it was mostly formed about 590 million years ago, about 76-100 million years before the Adelaide Fold Belt formed and billions of years after the Gawler Craton crustal block formed.

“The garnet is too young to come from the Gawler Craton and too old to come from the erosional Adelaide fold belt,” explains Sharmaine Verhaert, a graduate student in geology at the University of Adelaide who led the investigation.

Instead, the garnet likely formed at a time when South Australia’s crust “was relatively cool and non-mountainous,” says Verhaert.

Garnet is usually destroyed by prolonged exposure to waves and currents, so the researchers also realized that it probably appeared on the surface, even if it originally formed millions of miles away, millions of years ago.

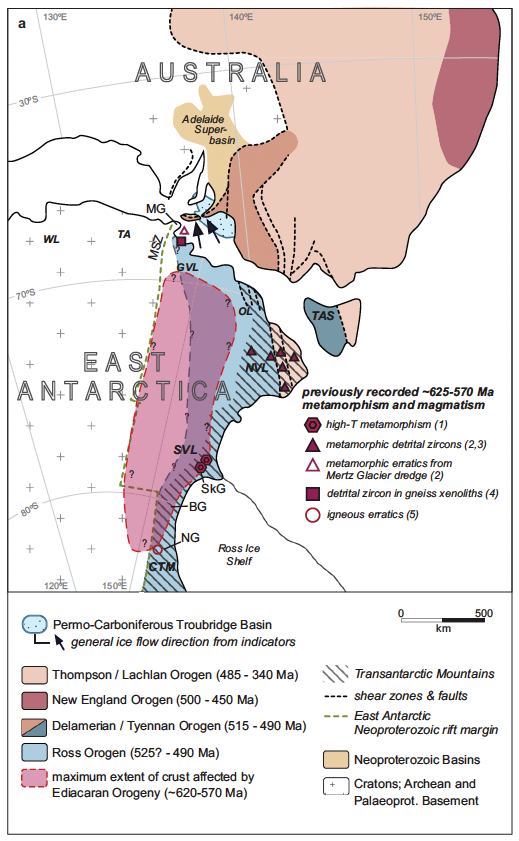

Their investigations revealed a grand solution, one that connects the pink sands of Petrel Bay to nearby glacial sedimentary rock layers and to distant garnet deposits previously found in an outcrop of the Transantarctic Mountains in East Antarctica.

Rock outcrops emerge from a thick layer of ice that otherwise completely hides the area below, making it impossible to sample the geology beyond the exposed peaks of a mountain range thought to lie below. The hidden mountain belt is thought to be 590 million years old, just like the garnet analyzed in this study, but researchers have not been able to get a good look at it.

By connecting the dots with indicators of ice flow in the glacial sedimentary rocks of South Australia, Verhaert and colleagues think that garnet-rich glacial sands were eroded from the Antarctic mountains – which have yet to see the light of day – by an ice sheet. moving north. -West during the Late Paleozoic Ice Age, when Australia and Antarctica were joined on the supercontinent Gondwana.

“The garnet deposits were then preserved in place in glacial sedimentary deposits along Australia’s southern margin,” explains University of Adelaide geologist Stijn Glorie, “until erosion. [once again] freed them and the waves and tides concentrated them on the beaches of South Australia.”

An epic journey through land and time.

The study was published in Earth and Environment Communications.